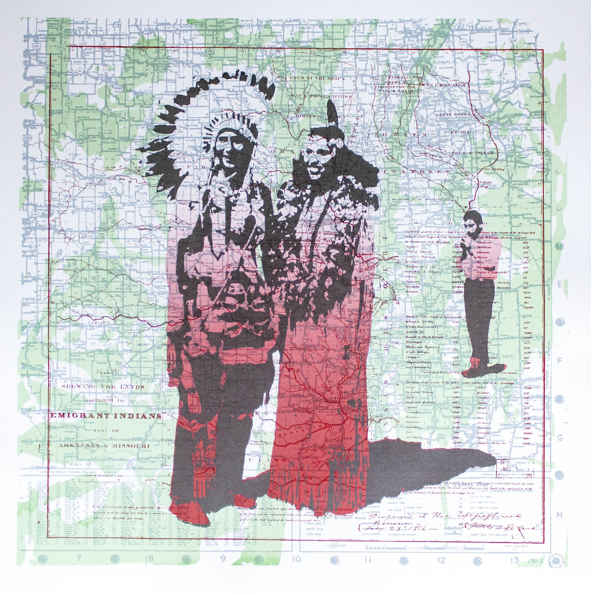

Bobby C. Martin / Courtesy photo

Bobby C. Martin’s paintings and prints are steeped in family history and in his Muscogee (Creek) heritage. For the past twenty-five years, old family photographs, uncovered from shoe boxes, bottoms of drawers, and tattered photo albums, have served as inspiration for his artwork, as well as an exploration into his own identity and what exactly it means to be Native.

“But You Don’t Look Indian…”, an exhibition of new paintings and prints by Martin, opens at Art Ventures on the Fayetteville square on Thursday, Oct. 4 and will be on view until Sunday, Oct. 28.

Native-themed Exhibitions

Four new exhibitions with Native themes will open in Northwest Arkansas in early October.

But You Don’t Look Indian… – This exhibition of new paintings and prints by Bobby C. Martin opens at Art Ventures on the Fayetteville square on Thursday, Oct. 4 and will be on view until Sunday, Oct. 28.

Borders and Boundaries: The Blurred Edges of Decolonisation – Running concurrently with Martin’s exhibition at Art Ventures, and curated by Martin and Robert Peters, this international exhibition includes some 30 artists from North American, Britain, Ireland and other parts of Europe explore ideas of colonial legacy, cultural appropriation, assimilation and decolonization.

Art for a New Understanding: Native Voices, 1950s to Now – This exhibition opens at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville on Saturday, Oct. 6 and runs until Jan. 7, 2019.

Native Visions Now: Contemporary Work of Indigenous Artists of Oklahoma – Organized by the Museum of Native American History, this exhibition opens Friday, Oct. 5 at Downtown Bentonville Inc., at the southwest corner of the Bentonville square.

The title of the exhibition, which is also the title of a large encaustic painting in the show, comes from a remark Martin has heard innumerable times, particularly when he exhibits at venues like the Santa Fe Indian Market in New Mexico or the Cherokee Art Market in Tulsa. Though he is one-quarter Creek on his mother’s side, Martin himself does not display overtly Native features.

“The title is a response to that phrase I kept hearing,” Martin said during a recent interview at his 7 Springs Studio near West Siloam Springs, Oklahoma. “When people say, ‘But you don’t look Indian,’ I want to ask, ‘What am I supposed to look like?’ To me, looking Indian is one thing, but being Indian is a whole different thing.”

Martin executed the painting using the ancient technique of encaustic, which involves laying down multiple layers of beeswax by pouring, dripping or brushing a beeswax/resin/pigment mixture. “But You Don’t Look Indian…” depicts the head and shoulders of his half-Creek mother. In the background, floating around is an abstracted soup of color and shapes — emerging from under the layers of encaustic wax, like memories — are a wide range of visual elements that symbolize the artist’s Native heritage. Some of these elements are personal and familial, like old family photos, Scripture passages written in the Muscogee language and even his son’s tooth. Other images are formal and impersonal, like a section of the so-called “Dawes Rolls,” the government document issued in the 1890s that lists Martin’s maternal ancestors by name, gender and quantity of Native blood.

“The painting has images of my family and even actual family DNA,” Martin said. “The Dawes Rolls represent the whole idea of blood quantum, and the whole weirdness you get into, talking about how you quantify how much Indian you are.”

It was on a trip to New York, and seeing one of artist Jasper Johns’ encaustic paintings of an American flag, that inspired Martin to try incorporating the encaustic process into his work. That proved to be a major breakthrough, technically and aesthetically, and layering of images and information has been a major element of his painting ever since.

Courtesy

“The physical properties of encaustic layering led to my being able to create this ‘soup’ of information,” he said. “I was able to put all this material in, then go back and scrape bits and pieces away to reveal things, like an archaeological dig. You dig through layers to reveal things from the past. For me, that was a significant thing.”

Martin did not aspire to be an artist while he was growing up in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. Nor did he give a lot of thought to his Native heritage. His mother did not take the family to traditional Indian activities or generally make much of their ancestry.

“It wasn’t really part of my life” he said. “I pretty much took it for granted.”

As a teenager, Martin’s main interest was music. He dropped out of Northeastern State University in Tahlequah and played guitar in several bands in eastern Oklahoma and Sacramento, California, and even owned and operated a recording studio in Tahlequah. He returned to Northeastern to finish his undergraduate degree and majored in studio art and Indian studies, which sparked an interest in identity and in “finding out who I really was as a Native person.”

Martin earned an MFA in studio art at the University of Arkansas, with a concentration on printmaking and drawing. It was in graduate school that he began working with family photographs and also embedding things like maps, hymns, scripture, Dawes Roll names and the like into his work.

Courtesy

“They are bits and pieces of information that also tell stories, beside the family history,” he said. “In some ways, they are unique to me, but maybe not so unique. They’re also pretty universal.”

After a stint as a graphic designer at the GIlcrease Museum in Tulsa, Martin was eager to get back into the studio. Since 2008 he has been a professor of visual arts at John Brown University. He enjoys working with students, and having the time and opportunity to make his own art. His work is in numerous museum collections, including the Gilcrease Museum and Philbrook Museum in Tulsa, the Sam Noble Museum in Norman, Oklahoma, the Hood Museum of Art at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, and many private collections.