Weight loss is the first sign of chronic wasting disease in cervids. Other symptoms include an abnormal gait, extreme thirst and salivation.

Photo courtesy of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission

Nathan Ogden believes it’s just a matter of time before he encounters the disease that is killing deer and elk before he can hunt them in Northwest Arkansas.

“I’m sure it’s here, because it’s over there and over there,” he said referring to chronic wasting disease. “It’s got to be here. We just haven’t killed one that has tested positive.”

Ogden, 40, said the disease is quietly killing animals as it spreads into the area. Hunting in Northwest Arkansas has become a suspenseful waiting game.

Chronic wasting disease is a fatal neurological disease that affects cervids, members of the deer and elk family. It was first discovered in Colorado in 1967 and has since spread to 26 states, including Arkansas.

Caused by misshapen proteins, chronic wasting disease is similar to mad cow disease in cattle. It is a slowly progressing disease, but infected animals will eventually become thin and demonstrate abnormal behavior. The disease is always fatal.

Nathan Ogden and the five other members of his camp are sure that they will soon harvest a CWD+ deer or elk. When Ogden built his cabin in 2006, he named it “El Sueño,” Spanish for “The Dream.”

Photo by Emily Franks

As soon as the disease was discovered in Arkansas in 2016, the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission hired its first veterinarian, Jennifer Ballard. Testing the area for the disease, Ballard’s team found that there was already a 23 percent prevalence in Northwest Arkansas.

Ballard established a wildlife health program to create a management plan for chronic wasting disease. The commission also organized public meetings to inform Arkansas residents and ease the apprehension of the state’s hunters.

Ford Overton, Chairman of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission, said that the town hall meetings were organized to address the public’s questions and concerns about the disease.

“As commissioners, we serve the citizens of the state of Arkansas,” Overton said. “We felt that it was important to provide an open environment format where anybody could show up and ask questions.”

Ogden’s camp is on Bernie Mountain, which lies on the Madison side of the Madison and Newton County lines. When the disease was announced in the area, Ogden started attending the agency’s public meetings to get informed.

Located on the edge of Madison County, Ogden’s camp is “rock throwing distance” from Newton County. As of Jan. 10, 2019, Newton County has had 373 confirmed cases of chronic wasting disease. Madison County has had 47 cases.

Photo by Emily Franks

The disease is caused by a misfolded prion, a protein that is highly concentrated in the brain. When cervids are exposed to the misshapen prion, the normal proteins in the brain start to misfold in a cascading way. The accumulation of the misfolded proteins in the brain causes the cells in the brainstem to die.

After a cervid is exposed to the misshapen prion through bodily fluids, it can take 12 to 18 months before the animal shows any signs of sickness. This delay between contraction and symptoms is one of the biggest challenges in managing the disease.

“Even before the animals look sick, they are shedding that misfolded prion,” Ballard said. “The infected cervids expose a lot of animals to the disease before they themselves show symptoms of it.”

The delayed symptoms include weight loss, excessive drinking and an abnormal gait and posture.

“The infected animals show a lot of the signs that you would expect if your brain isn’t working right,” Ballard said. “They lose their fear of humans, and other animals exclude them from the group. Once they start showing signs, the progression to death is usually pretty quick; it just takes a while to get to the point where they are displaying symptoms.”

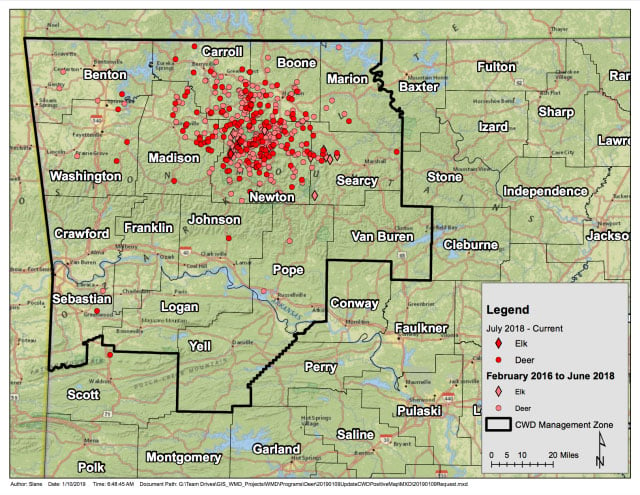

All 605 cases of the disease in the state have been found in Northwest Arkansas, with over half of the cases in Newton County.

The CWD Management Zone was established after the first case of chronic wasting disease was found in Arkansas to designate counties that must adhere to the disease management regulations. As positives have been found in additional counties, the zone has expanded with every hunting season.

Photo courtesy of the Arkansas Game and Fish Commission

Jimmy Dixon hunts on the Gene Rush Wildlife Management Area, which is about 15 miles west of his home in Jasper. Hunting in the heart of Newton County, Dixon was not surprised when the seemingly healthy deer he harvested on the first day of this past rifle season came back positive for chronic wasting disease.

“I wasn’t surprised that my deer had CWD,” Dixon said. “I had already talked to other hunters who had harvested deer earlier in the season, and a good number of those deer were coming back as CWD positive.”

Though there has never been a human case of chronic wasting disease, Dixon was happy to comply with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s recommendation to avoid consuming meat that comes from an infected cervid. Similar diseases, such as mad cow disease, have made the jump from cattle to humans, so many fear that chronic wasting disease could eventually do the same.

“Even though there’s never been a human case, we still recommend that people take due caution because prions evolve,” Ballard said.

The CWD Management Zone was established to help contain the disease by executing management strategies within high-risk counties. The zone designates counties with positive cases and counties within 10 miles of a positive case, which takes into account the natural movement of the deer.

The commission has enacted several regulations in the zone to slow the spread of the disease. Hoping to use hunter harvest to break the transmission cycle, they have removed antler point restrictions and increased the bag limit in the management zone.

Rolling hills are dotted with grazing cattle on the Madison and Newton County line. The steep geography of the region has naturally isolated the disease infected population.

Photo by Emily Franks

The wilderness agency has also implemented restrictions on moving carcasses out of the zone to slow the spreading of the disease through human movement.

“We can’t stop every animal at the county line, but we can affect how much humans participate in the movement of the disease,” Ballard said.

Since the southeast Delta is home to Arkansas’ premier deer hunting, the aggregation of the disease in Northwest Arkansas might seem perplexing. However, the concentration is no coincidence, Ballard said.

Because animals breed as they move, gene flow is an indicator of animal movement. A state-wide assessment of the disease has shown that the genes of the cervids in Northwest Arkansas are different than the genes of many of the surrounding populations, indicating a lack of gene flow.

“It seems that that population has isolated itself,” Ballard said. “We think it’s probably natural isolation caused by the steep geography. The disease is not spreading out of that zone very quickly because the deer don’t move out of that zone very regularly.”

Ballard said that while the isolation of the infected population has helped slow the spread of the disease, it also probably delayed initial detection.

“We wouldn’t have found it unless we tested in exactly the right spot,” she said.

Another challenge with the disease is its slow response to management, as delayed gratification is hardly motivating.

“It could take seven or 10 years before we start to see the benefit of our management plan,” Ballard said. “It’s hard to keep staff and resources focused when the consequences won’t come for a long time.”

A homemade deer stand looks over the steep landscape of Ogden’s land. Ballard and her team are relying on hunter harvest to help them manage chronic wasting disease in Arkansas.

Photo by Emily Franks

Ballard encouraged Arkansas outdoorsmen and women to take advantage of the commission’s transparency on the issue.

“We’ve tried to be very open about the whole situation,” Ballard said. “We share everything we know about CWD in the state. I would encourage people to check out our website, come to our public meetings and stay informed on the issue.”

Testing brain tissue is the only way to diagnose chronic wasting disease. Brain tissue cannot be taken from living deer, which makes it much harder for biologists to kill off the disease.

“Since you can’t test live animals, there’s no getting rid of it without killing everything,” Ogden said.

Because species extermination is both impossible and unwelcome in the area, Ogden said that chronic wasting disease is something that hunters are going to have to learn to work around.

Ballard said that the chance of eradicating the disease in the state is grim, but she’s hoping that ongoing national research will yield new ways to combat the disease.

“We’re definitely not going to eradicate this disease with the tools we have now,” Ballard said. “We hope that more tools and new technologies will become available to help us address CWD in the future. But for now, we can only hope to stabilize the disease through collaboration with hunters.”