Scott Lafontaine stands next to brewing equipment in the University of Arkansas’ onsite brewery. (Brian Sorensen)

Scott Lafontaine stands next to brewing equipment in the University of Arkansas’ onsite brewery. (Brian Sorensen)A professor at the University of Arkansas is working to understand if rice can play a bigger role in beer-making. He is particularly interested in seeing how the grain can improve the quality and acceptance of non-alcoholic alternatives.

Scott Lafontaine is an assistant professor in food chemistry, having joined the school in October of last year. He previously worked under renowned fermentation scientist Dr. Tom Shellhammer at Oregon State University. He later made a brief stop at the University of California, Davis before expatriating to a German school dedicated to the science of brewing.

The New Jersey native first became interested in beer while completing his undergraduate and master’s-level studies at Kean University.

“The program I was enrolled in – biotechnology – was intertwined with pharmaceutical development,” said Lafontaine. “I realized it wasn’t what I wanted to do in the long run. I discovered you can harvest yeast to make alcohol, and I reached out to a craft brewery in the area called Cricket Hill Brewery to see if I could intern with them. They hired me, and I started learning how to produce beer. From there I started to home brew.”

He went on to study environmental toxicology as a part of his master’s studies at Oregon State. While there he investigated how air pollution originating from China rode the jet stream across the Pacific Ocean and into the United States. It provided another segue into beer.

“When I obtained my master’s degree in 2015 the craft beer market was still on its upward rise,” said Lafontaine. “I reached out to Tom [Shellhammer] and my skill set fit with what he was doing with his analysis of hop aromatics. IPAs were driving industry growth, and people were looking for the aromatics of hops without the bitterness. The same instrumentation I was using to analyze volatile compounds in air pollution was also important for studying hop oils.”

Lafontaine’s interest in non-alcoholic beer began after leaving Oregon State with a Ph.D. in food science. In July 2019 he arrived at Dr. Hildegarde Heymann’s laboratory at the University of California, Davis, where he studied the chemical and sensory characteristics of non-alcoholic beer. He then received a Humboldt Postdoctoral Fellowship and moved to Berlin, Germany, where he worked in the Department of Special Analytics at the Versuchs- und Lehranstalt für Brauerei (VLB). His focus there was on finding ways to promote flavor stability in non-alcoholic beer.

Working in Europe provided a closer look at the emerging consumer trend of non-alcoholic beer.

“I could see the writing on the wall,” said Lafontaine. “Non-alcoholic beer was about to take off, but there wasn’t much research done at that point. If a beer travels a long distance and sits on a shelf for a period of time, are there things in hops that you can use – such as enzymes – that can influence its flavor stability? Are there certain compounds derived from hops or malt that impact flavor during distribution? Those were some of the questions I was asking.”

The University of Arkansas started its brewing certificate program in 2020. It consists of courses from the Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences, the Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences, and the College of Engineering. The program’s first two students completed the 15 hours of required coursework last year, and the program continues to see an increase in student interest.

(Photo by Brian Sorensen)

(Photo by Brian Sorensen)Lafontaine – whose brother-in-law grew up in nearby Elkins – took note of the program when looking for his next career move. “I thought maybe I could fit in there,” he said. “It appeared to need a boost of energy, and somebody with the background to help define its path forward.”

Arkansas’s rich agricultural history was also a draw to the Fayetteville campus for Lafontaine.

“A lot of schools want a brewing program,” he said. “But you have to have an agricultural product to be successful with one. Arkansas has rice, which is a very underutilized crop when you look at how brewers treat it right now. Most brewers use it as an adjunct [a supplement rather than an essential ingredient]; almost as an afterthought. But there’s so much more potential when you look at how breeders are working with aromatic rice varieties. And since I also wanted to diversify myself from my former advisor, who was working with hops, I decided Arkansas was the right fit for me.”

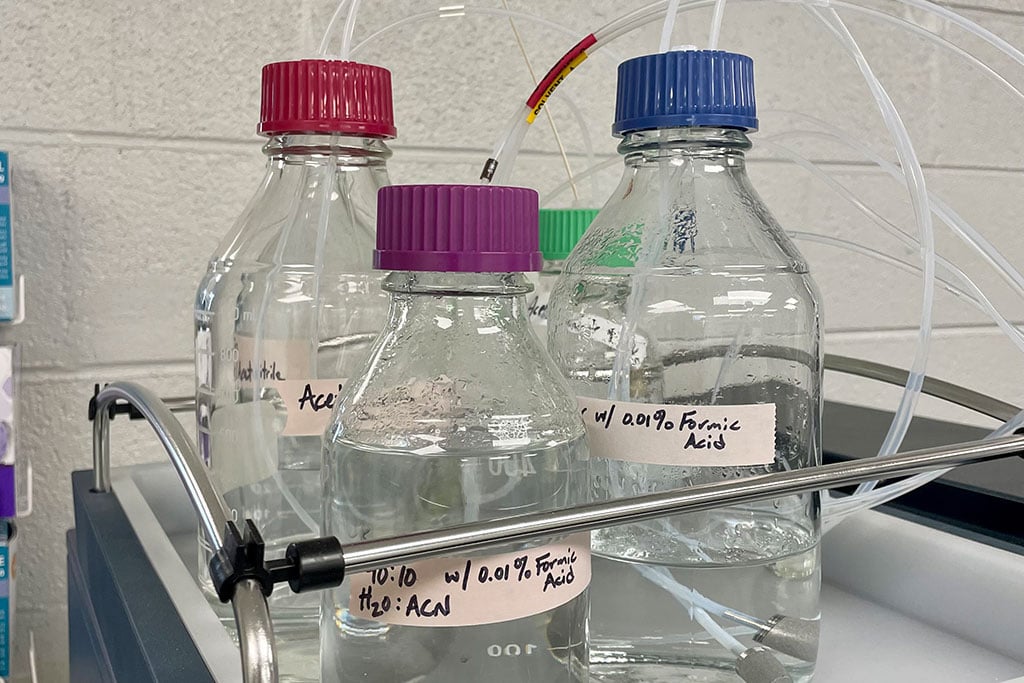

Lafontaine taught a couple of courses during the spring semester, his first full semester in Fayetteville. One of those courses was “Introduction to Brewing Science,” a three-hour class based in brewing theory that featured guest speakers from the industry. This fall his students will design beers and analyze them for alcohol content, bitterness, and other important measurables. There is a small but impressive brewery on campus outfitted with stainless steel vessels from brewing equipment manufacturer Ss Brewtech. The value of the laboratory equipment used to analyze the finished product exceeds that of most mid- to large-sized homes in the area.

Lafontaine’s research on rice’s use in brewing is in its early stages. He’s hopeful that he can identify new and exciting ways to use the grain in modern brewing practices.

“We’ll be looking at different rice varietals to learn if we can get different extracts and unique flavors from them,” he said.

ARoma 22 is one such varietal. It is a jasmine-type aromatic rice developed by the Arkansas Rice Breeding Program, which is a part of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture. Over the last ten years the program has developed a total of sixteen rice varieties, of which three have been aromatic lines.

Lafontaine said most brewers that use rice do so to increase the amount of fermentable sugar in their beers without adding much to the finished product’s flavor profile. Industrial brewers such as Anheuser-Busch mill rice and boil the grain to gelatinize its starch before mixing it with barley so that the enzymes in the barley can make it fermentable. The goal is more fermentable sugar to produce more alcohol without creating additional flavor characteristics.

“For them, even a small gain in extract [fermentable sugars] would be a good thing when considering the scale on which they brew,” he said, pointing towards significant cost reductions for large brewers. “If certain varieties of rice are performing better from that perspective, it’s something we want to know.”

But there are other ways to use the grain in beer-making. It can also be germinated, which essentially turns it into malt and makes its use comparable to barley. Modern brewers aren’t typically using it in that way, but there is underlying potential for flavor and color contributions beyond the existence of neutral-tasting fermentables.

(Photo by Brian Sorensen)

(Photo by Brian Sorensen)“Nobody has really looked at germinating rice from a brewing perspective,” said Lafontaine. “There are only a couple of research papers that looked at European varieties, but nobody has looked at varieties from the U.S. What we’re finding is that some rice varieties are performing pretty close to barley from a chemical perspective – protein, enzymatic activity, or extract. We are looking to see if there’s something to it.”

There’s also potential use for rice in the production of non-alcoholic beer. Most non-alcoholic beer is made with barley, which creates an overly-malty flavor impact in some products.

“If we can think about how to get mouth feel characteristics while dialing back some of the ‘worty’ character by using rice, we can make non-alcoholic beer more approachable,” said Lafontaine.

That’s good news for an industry segment that has already seen substantial growth in recent years. According to GMI insights, the worldwide market for non-alcoholic beer grew to $22 billion in 2022. It is expected to reach $40 billion by 2032.

Fueling the growth of the product is an increased awareness of personal health and the need to reduce intake of alcohol. Shifting some portion of beer consumption to non-alcoholic products allows consumers to experience the taste of their favorite beverage without the negative consequences of overindulgence. The success of brands such as Athletic Brewing – which has captured more than half of the non-alcoholic beer market – is an indication that quality and acceptance have both increased over time.

During his time abroad, Lafontaine saw how Europeans adopted non-alcoholic beer as an alternative to be enjoyed at least some of the time. He thinks the same can be accomplished here at home.

“In Europe you can find a good non-alcoholic option at nearly every bar and restaurant you visit,” he said. “Why can’t the same be true in America?”

Hopefully his research on rice and its potential to improve the taste of non-alcoholic beer will make that a real possibility here at home.

This article is sponsored by First Security Bank. For more great stories of Arkansas food, travel, sports, music and more, visit onlyinark.com